When a Botswana delegation visited the United Kingdom in March this year to dissuade British MPs from voting for a bill that bans the importation of hunting trophies, representatives from Mababe – a small settlement and a significant player in safari hunting – were left behind.

This exclusion baffled village chief, Kgosi Kgosimontle Kebuelemang, and points to a larger systemic problem. Not only are impoverished communities residing in wildlife-rich areas often excluded from meaningful discussions, but the economic benefits also they get from trophy hunting are limited.

In an area teeming with wild animals, Mababe residents – and other communities on the edge of the Okavango Delta cannot legally rear livestock or farm crops.

This is why the Department of Wildlife and National Parks allocates hunting quotas using a participatory and science-based process. According to data from Elephants Without Borders, a cross-border conservation NGO, participating concessions were allocated a quota of 1,050 elephants and dozens of other wild animals between 2022 and 2024.

Under the guidance of the Community Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) Policy and the Technical Advisory Committee (which comprises of representatives from the wildlife and tourism departments), community trusts negotiate controlled hunting agreements with hunting operators. In turn, these operators market the allocated quota to European and American safari hunters who then look so thrilled after killing the wild Jumbos and arrange them into a submissive posse for their own preserve self-gratification. The Ministry of Environment and Tourism did not respond to media questions.

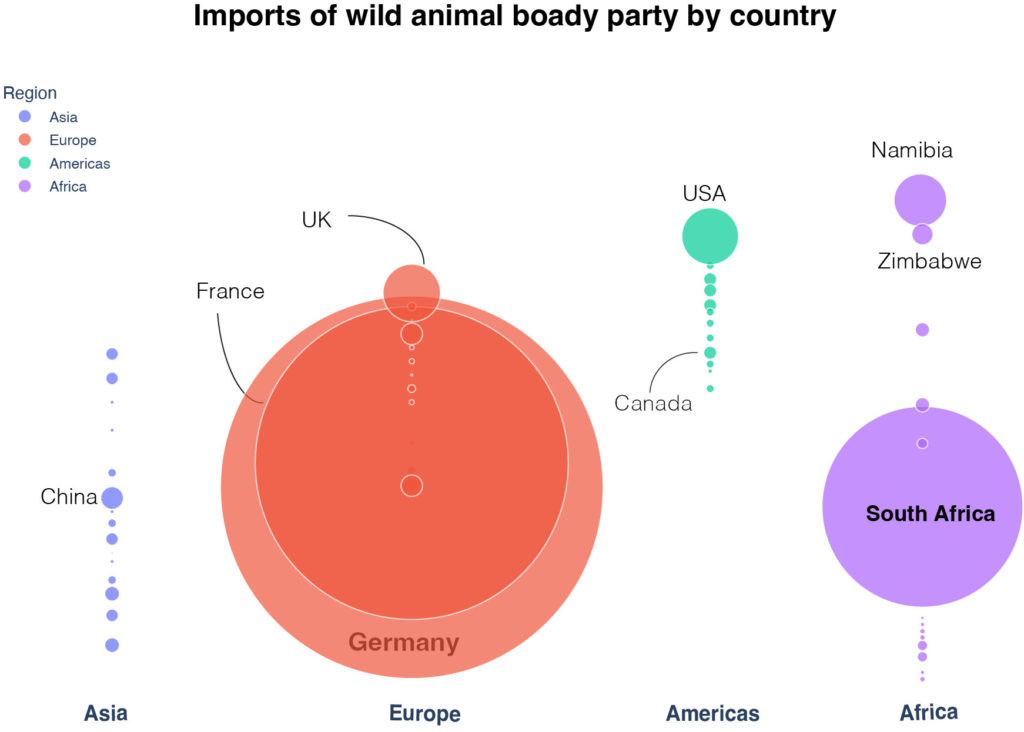

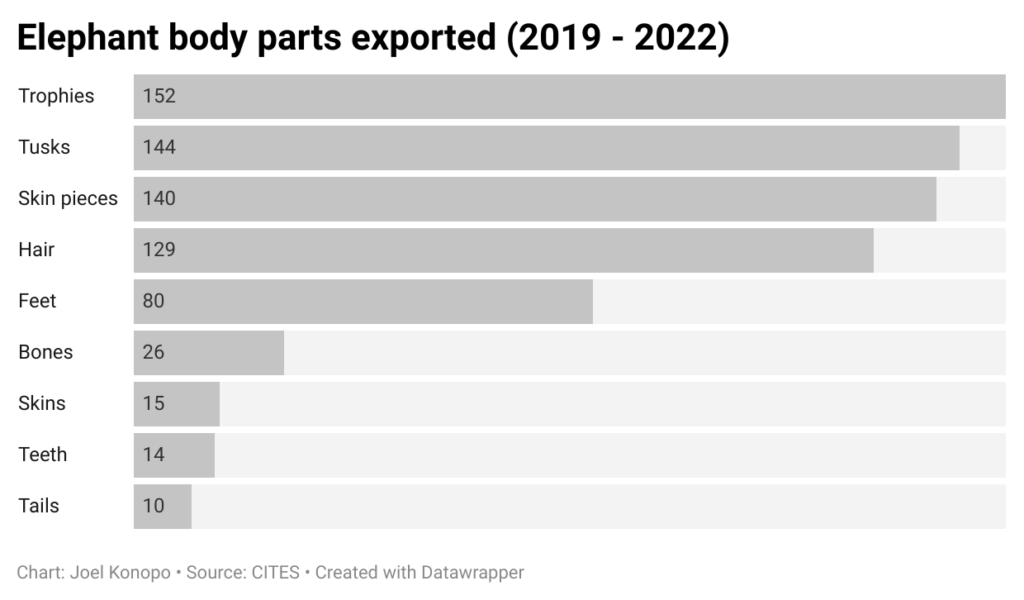

This trade caters for a small but wealthy clientele of big-game hunters, most of them westerners. According to the CITES, these hunters took more than 60 lion trophies — heads and fur — to the United States, Europe, and Asia between 2019 and 2022. Some 1000 elephant feet also left Botswana the same way to be prepared by taxidermy and used as souvenir foot stools.

There is no doubt that wildlife holds significant importance for the livelihoods of vulnerable communities. However, the essence of trophy hunting boils down to a bizarre and selfish desire – to slaughter wild animals – justified by arguments rooted in flawed ecological and economic reasoning.

False and exaggerated benefits

President Mokgweetsi Masisi and his Minister of Environment and Tourism, Meshack Mthimkhulu, have argued that recreational hunting has economic incentives and promotes conservation. While that may be true on paper, the reality is that the economic evidence in favour of trophy hunting in Botswana is scanty. On some websites marketing elephant hunts, the price for a single bull ranges from US$90 000 to US$100 000 (approximately P1.24 million to P1.36 million respectively). Sadly, Mababe Community Trust receives only a fraction of that money – around P85,000 to P220,000 per bull (around US$7 000 to US$17 000), from predatory hunting operators who dictate the price for the game.

This skewed financial benefit is deepening poverty in communities that rely on wild animals.

For example, a tenth of Mababe’s 381 inhabitants are on destitute programs – a 4 percent increase from 2017 when there was no hunting.

That reality is also illustrated by conservationist Adam Cruise who, in his book, “Trophy Hunting in Botswana”, posits that poverty levels are much higher in CBNRM households, compared to the rest of the country. Cruise argues that while the average rural poverty in Botswana stands at 25 percent, it is much higher in Chobe and Northwest regions. The UN human development index data also supports this claim.

Save for the government, everyone agrees that community benefits from trophy hunting are overly exaggerated. There is no transparency in the sale of the quota and hunting operators have no interest in empowering community trusts to develop to a point where they can directly negotiate with hunters in the future.

In 2022, Mababe was allocated a quota of 15 elephants, which premier hunting operator, Johan Calitz, bought for around US$250 000 (approximately P3 million) to sell to big-game hunting enthusiasts. In the process, he made around US$1.8 million (approximately P24 million).

“Calitz does marketing of elephants for us,” remarks Kebuelemang, referring to the South African hunting operator who acquired hunting rights of concession known as NG41 in northwestern Botswana.

In concurring with Kebuelemang, Kgosi Gokgathang Moalosi of Sankoyo which controls the NG34 concession laments that “We are kept in the dark about the prices.”

Unlike Kebuelemang, Moalosi was part of a 40-member delegation that splashed P18 million to Westminster – led by Mthumkhulu, that got to meet some British MPs. Sankoyo is reeling from years of swindling by hunting operators, who, according to tourism experts, pocket more than 500 percent of sale proceeds. Moalosi recalls an incident in 2014 in which a hunting operator offered P30,000 (approximately US$2250) for three elephant bulls.

“You see, this was an insult,” he says mournfully.

Sankoyo is currently not engaged in hunting activities but intends to resume them once their concession (NG34) is allocated a quota. This time around, the community plans to deal directly with big-game hunters.

Reaobaka Mbulawa, a tourism entrepreneur and politician, is incensed with the current arrangement.

“Why do we need a middleman?” he wonders loudly, more to himself than to anyone else.

His theory is that colonial thinking, which undermines the worth of Batswana, is still pervasive in society.

“I have seen a single bull going for $300 000.”

Masego Community Conservation Trust in Bobirwa region of eastern Botswana has endured more “insults” from hunting operators than Sankoyo. As Dominic Davidson Mapetla, a

former board member reveals, naked dishonesty is also built into such insults.

“A hunting operator makes an offer so high that he discourages others from continuing with the bid. Days later, he returns to negotiate a lower price. That’s Mafia style,” says Mapetla, further revealing that some board members connive with the middlemen in the execution of this scam.

When he raised objections about the chicanery of hunting operators, Mapetla was unceremoniously removed from the board.

In 2021, Masego Community Conservation Trust sold a quota that included 30 elephants and other wild animals for less than US$90 000 to an unspecified hunting operator. Mapetla alleges that some board members were beneficiaries of this deal.

Gaining business experience by community trusts is supposed to be an additional benefit from these transactions. In part, the CBNRM policy recommends skill transfer to empower communities such that they can conduct independent sales in the future. The reality though is that there is no mechanism to facilitate that recommendation.

Professor Joseph Mbaiwa, a professor of Tourism Studies who heads the University of Botswana’s Okavango Research Institute, says that community trusts conduct tourism business in a laissez-faire approach. He likens them to someone selling their house but doesn’t know its market value.

“They are selling tourism products without necessarily knowing the

economic or tourism value of these products,” says Mbaiwa, adding that

government should be more methodical about empowering communities.

“Government is protecting local horticulture industry by banning

importation of vegetables. There is need for this kind of protection and

empowerment in tourism.”

Corruption and Mismanagement

Framing this issue purely as one of beneficiation to communities – important as such beneficiation is – leaves us ill-equipped to address complex and nuanced issues of corruption, bribery, and mismanagement.

Tcheku Community Trust in northern Botswana is supposed to benefit over 600 households in Kaputura, Tobere and Kyeica. However, an internal audit report replete with evidence of embezzlement and corruption reveals that income from trophy hunting quota sales went to the hunting operator and some Trust staff members instead of the communities.

The Trust which, manages a hunting area known as NG13, received US$69,400 (around P946,000) for a hunting quota in 2019 from hunting operator known as Old Man’s Pan, owned by the late business mogul, Derek Brink. However, it neither negotiated a higher price nor engaged a government-designated advisory committee on pricing when that is a requirement in the Trust’s Notarial Deed of Amendment. Only in 2022 did an audit report recommend an investigation into a suspicious relationship between Old Man’s Pan and Board trustees after the Trust manager suspiciously reduced the price of the hunting quota without engaging the technical advisory committee.

It has also emerged that some trusts that receive millions of Pula from hunting operators divert the funds to administrative and legal costs instead of using it to develop the community. Resultantly, little income goes to communities (some households receive as little as P500 or US$37 a year) and the supposed incentive severely lessened. Making the situation worse is that some village headmen have parallel interests as they run their own lodges, camps, and mobile safari. This constitutes obvious conflict of interest, but such conflict appears to be more extensive.

A conflict of interest?

Prof. Mbaiwa, who advises the government on hunting, has a business relationship with a professional hunter called Jeffrey Rann. The pair co-owns Xudum Okavango River in which Mbaiwa has a 25 percent stake. Mbaiwa defends this relationship by asserting that he acquired this shareholding in 2019 when he faced imminent expulsion from UB. He explains that his aim was to take advantage of a citizen economic empowerment programme by leasing NG29, a photographic safari concession.

“But the deal fell off after the government refused to lease NG29 to us,” says Mbaiwa.

“I was vulnerable and job-seeking but the whole deal failed.”

He explains that he no longer runs a business as he returned to the university.

The law is also weak

Part of the problem can be attributed to the absence of legislative instruments that can adequately protect the economic interests of communities in wildlife-rich areas. While the CBNRM Policy of 2007, the Tourism Policy of 2021 and the Wildlife Conservation Policy of 2023 articulate programmes that can enable communities’ meaningful participation in the tourism business, they don’t go far enough. More effective would be a more comprehensive CBNRM Act as well as a trophy hunting policy that would thwart corruption and bribery within trusts. Prof. Mbaiwa says that the current CBNRM Act is “extremely general” as it covers many CBNRM activities.

“The Hunting Act should only focus on hunting and be specific on issues of hunting, including penalties on illegal hunting.”

African trophy hunting may be an expensive hobby that only a few can afford, but it is true that it is also a big business for hunting operators. The issue has been severely politicised, with ruling Botswana Democratic Party embedded in critiquing former president, Ian Khama and government hunting stance taking that shape. As Jorge Luis Borges dreamed of endless libraries, minister Mthimkhulu and President Masisi dream of endless rebuttals of everything that Khama says.

source here